Finding Balance

My original plan was to post about Force, Stress, and the Hoof at this point. In fact, I prepared and (briefly) posted just such a blog entry -- one filled with mathematical calculations and numbers -- on my website. But I wasn't satisfied with it, for very important reasons. So the post appeared, disappeared, and then reappeared with changes over a span of several days as I wrestled with my goals for posting it. It wasn’t a small matter that I put it up to begin with . . . and it wasn’t a small matter that I finally decided to take it down. Both things matter enough — to the goals I have for writing this blog to begin with, and to the goals many of us have for our horses — that I wrote this blog entry to express my struggle and the reasons for my final decision. Then, when I get back to hooves and stress, we’ll be starting on the right foot this time.

The slogan Jo (my business partner) and I use for our horse work is “Balance, Center, Connect.” This is the logo we designed for the first horse program we ever ran, which was at that time part of the work in which our non-profit, Tapestry Institute, was engaged. We coined the phrase to refer not only to our horses’ own best functional states, and to the states that allow us to have our best riding experiences, but also, purely and simply, to ourselves as human beings.

We all know it’s difficult for a person who’s not physically balanced to ride well. They continually throw their horse off-balance with their own off-kilter weight (which produces the “eccentric load” I talk about in my biomechanics seminars), accidentally asymmetrical hands and feet, or body stiffness that translates itself right into the horse. The same is true of being physically centered. And of course we need just the right amount of physical connection with the horse we’re riding to communicate responsibly as well as effectively.

But emotional balance matters, too. Who among us has not had a miserable time riding, fussing with our horse for being “difficult,” only to realize with a sudden pang of guilt that we went out to ride that day already angry or upset about something else? An emotionally unbalanced state communicates itself to our horses just as freely as it does to the humans around us, who can at least use spoken words to ask us to “lighten up” or “take a walk to calm down” before dealing with, and upsetting, them further.

But emotional balance matters, too. Who among us has not had a miserable time riding, fussing with our horse for being “difficult,” only to realize with a sudden pang of guilt that we went out to ride that day already angry or upset about something else? An emotionally unbalanced state communicates itself to our horses just as freely as it does to the humans around us, who can at least use spoken words to ask us to “lighten up” or “take a walk to calm down” before dealing with, and upsetting, them further.

When it comes to understanding how horses move and support themselves and their riders, it’s also important to balance different types of knowledge. But doing so is extremely difficult because of our culture’s deeply-embedded assumption that logic, reason, and mathematics are the most valid ways of understanding reality. “Factual” information is seen as trumping any other type, “science” is seen as producing the most reliable facts, and information that is mathematical is seen as being the “best” type of science. Here’s an example of the result of this type of worldview.

Hilary Clayton, Ph.D., at Michigan State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, has carried out studies on the biomechanics of bits. Clayton is a solid researcher who holds excellent credentials and has published a number of books. But her work can be a bit daunting for many people to read. Her biomechanics and physiology books, in particular, are ones I would personally select for my students to use if I was teaching a graduate course in biomechanics, but be reluctant to recommend as an easy-to-use resource for a rider who doesn’t want to get a graduate degree. Yet Clayton gets her work “out there” in clinics and talks — and is frequently misunderstood by people who are looking for “facts”, particularly mathematical ones they can hang their hats on with pride of knowledge.

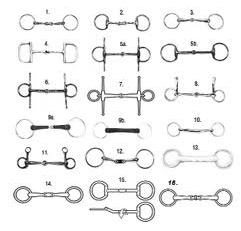

Clayton’s work on horse bits was summarized and reported in Horse Science News in an article titled “Myler Bits Act Differently on Horses.” More than half of the three-paragraph summary was devoted to mathematical data, such as: “The jointed snaffle and Boucher bits both averaged 3.3 centimetres (1.3 inches) away from the teeth, whereas the Myler snaffle lay just 2 cm from the premolars. The other two Myler bits were located even closer, at 1.3 cm from the premolar teeth.” A reader studying this report is left with the comforting notion that “something important” has been learned about bits, particularly about the place in the mouth that myler bits sit compared to other bits, and that single-jointed snaffle construction and rein tension are somehow relevant  factors. At the same time, I think it would be difficult for most riders to apply any of the information presented. I also think, from my years of doing public education with Americans who both respect and dislike science (thanks in large part to nasty grade- and high-school experiences) that most of the people who couldn’t make heads or tails out of what to do with this information would assume the problem was their own — that they didn’t know enough, or weren’t smart enough, to see at once how to apply it.

factors. At the same time, I think it would be difficult for most riders to apply any of the information presented. I also think, from my years of doing public education with Americans who both respect and dislike science (thanks in large part to nasty grade- and high-school experiences) that most of the people who couldn’t make heads or tails out of what to do with this information would assume the problem was their own — that they didn’t know enough, or weren’t smart enough, to see at once how to apply it.

The trickier part of this is that I also know, from long experience, that there are people who do bitting clinics as part of their general horse business who, when they come across this numbers-filled article, will figure out a way to say that the figures support whatever view of bits they propound in their clinics. If you think people don’t do that, just watch the labels on (and ads for) products in the grocery store the next time there’s big news about a scientific study linking a particular nutrient or compound to some aspect of staying healthy. And it makes sense if you think about it — as long as the “facts” have been appropriately represented in the p.... And that, as the PLoS Medicine article I just linked to shows, is the rub, right there.

On the other hand, take a look at this article summarizing Clayton’s bit research at Horse Journal on the Equisearch website. (That’s not a rhetorical statement. I really recommend you read the material to which I’ve linked.) This article, titled “Dr. Hilary Clayton Offers Many Prescriptions for Bits,” has an entirely different theme: “Dr. Hilary Clayton has been studying the way bits act on horses’ mouths for more than 20 years. But even after all those years of systematic research, she still says that ‘finding the right bit is more a matter of trial and error than a scientific process.’” The italics are my addition, to highlight the part of this statement I find particularly meaningful. The article then goes on to list some generalized findings that will come as a surprise to many horsepeople — one of which is that many horses prefer smaller-diameter to larger-diameter bits because their mouths are smaller than we think they are — and then quotes Clayton categorically stating that the rider has to figure out which bit their own horse is most comfortable using: “‘So the size and the shape of the bit is individual to every horse, meaning you have to keep trying until you find a bit they’re comfortable with”. This is repeated in the article’s last line, which concludes: “. . . Clayton still believes that finding the right bit for your horse is a matter of simply trying different bits.” Please notice that this research scientist is emphasizing the real value of experiential knowledge here, rather than “fact”-based knowledge, in two ways: (1) the rider is to use a personal trial-and-error method to try different bits and see how each one works, and (2) the rider is to assess each bit tested by using their own individual perception of how comfortable their horse is with that bit in its mouth.

You don’t have to look far to find publications in which people who claim “horse expert” authority denigrate the very idea that horse “comfort” matters or that humans can assess a horse’s comfort. Further, such “experts” claim to use science, of all things, to give authority to their denigratation of experiential modes of understanding and to support their own fact-based system of information as not only best but also the only reliable source of knowledge. This is what leaves horsepeople feeling stuck, unable to get themselves and their horses out of situations that don’t feel right.

Yet here is a highly-credentialed research scientist who’s emphasizing experiential learning, the significance of a horse’s comfort, and the reliable ability of a horse owner to tell if their horse is comfortable or not. Given that the non-scientist “bit expert” who denigrates the horse owner’s experiential learning is claiming the authority of science (supposedly), then should not the actual scientist have the higher authority in this case? If so, then the paradoxical situation is that it is the scientist who turns over the tables on what type of knowledge has real value, placing the final authority squarely in the hands of a rider and the responses of her horse. And if that rider says, “But I don’t know about bits,” then look again at the article I linked to and you will see that it addresses this issue. Clayton points out the salient factors that usually impact bit comfort, that we need to pay attention to, including how high or low in the mouth the bit rides, whether it’s single jointed or has a flat area over the tongue, whether it touches the roof of the mouth, and the importance of paying as much attention as possible to the size of the mouth cavity since it’s not directly comparable to the horse’s body size. In other words, there are pieces of “factual information” she’s learned in 20 years of bit research, and she’s passing those on in order to give riders information about what to look for as we run our own tests. She is teaching us what to look at, how to see.

So that then we can make our own decisions.

That’s what science is about. It’s about learning what factors exist, since usually we aren’t aware of even a tenth of them in normal practice. It’s about learning which factors that we never even thought of are really important to pay attention to. And then it’s about learning how to integrate information about these factors into a much larger scheme of understanding the subject so that we can make personal decisions that are wise and informed. This is real science — which, interestingly, is based on trial-and-error (which is called “experimentation”) and personal assessment of results (which are called “sense-data”) — the two specific methods Clayton recommends horsepeople use to select the right bit for their own personal horse. Oddly enough, the fact-based, supposedly “science”-based system we find so often in the horse world, that tells us horse comfort is an illusion, that riders can’t possibly decide what’s best for their horse (but must hand over decisions to Experts), and that all horses in a certain discipline “must” use a particular bit because “we know” that bits work in such-and-such a way is actually not scientific at all. And I am saying that as a scientist with a doctorate from a major university, who has participated in policy discussions about the nature of science and of communicating science to the public in formal and informal education at the highest levels possible in the US.

All this being the case, my goal for this blog and for my seminars, both, is to share what I know about horse biomechanics and horse movement to help people learn how to see their horses better. I want to share information that helps riders see and appreciate the really astonishing power and subtlety of response that exists in a horse’s systems of adaptation to stress, and to learn what to look at when they assess how their horse is moving. I want to help people better understand the basic biomechanical adaptations of their own human bodies, to feel how subtly but profoundly those operate, and then use that information to understand the operation of those same systems in their horses’ bodies. And I want them to be able to use this information, even twenty or thirty years from now, with everything else they know about horses in general and their own horse in particular, to feel confident enough about their own authority to tell a trainer, when necessary: “No. I realize the method of moving you use on horses may work for many, but it’s not good for my horse. Thank you for your efforts to date, but I am discontinuing his training with you.”

The problem with my original blog post on force, stress, and the hoof was that it focused on numbers. It focused on calculations. It focused on apparent absolutes that really do not exist except in the most artificial situations imaginable (where, for example, a horse is literally not moving a muscle). And in doing all these things, it took us all to exactly the place I don’t want to go.

The first time I took it down, it was because I thought about all this. What I did was put it back up with a paragraph added near the beginning: “I want to say at this point that calculating, or even measuring, force in a living body is extremely difficult — sometimes impossible — for practical reasons having to do with the incredibly responsive systems of animal support, balance, and locomotion, and the fact that contraction in even a single muscle is generally along a wave that makes its force vectors change rapidly and dramatically. So the goal of this blog and the next is to look at things in just enough detail for you to get a working idea of the levels of load on horse hooves, and the sorts of things that impact those loads for better or worse.”

But the post still bothered me. Because I knew very well that my disclaimer — which was the real point of all the horse biomechanics work I do — was going to be monumentally outweighed by the correct but almost meaningless calculations I had gone to such great lengths to explain, about force and stress in the hoof. And finally I realized I have to go about explaining this a different way — one that focuses on the issues of subtlety and responsiveness in the horse’s living systems of adaptation. One that leaves the numbers out unless there’s an essential reason for them, and then makes very certain to keep them in perspective. One in which all the different ways of knowing about and understanding how horses move are in balance and connected.

I close with the same Calvin and Hobbes cartoon with which I opened my ill-fated post of hoof stress calculations, this time focusing your attention on all the different ways of knowing that Hobbes combines to be an effective tiger. The laws of physics and the principles of biology are important factors, but so are art and ethics. All I can say is: right on.

So now I’m in balance again, not focused all to one side of things with purely intellectual and mathematically-based knowledge. And I’m centered once more, squarely in the framework of the goals I have for this blog, my seminars, and my life work in general. The result, I hope, is that I’m better connected to you, the reader.

And NOW we can go on to consider force and stress in the hoof . . . this time, in a way that has a little more meaning, and meaning you can use.

The Rider Marketplace

International Horse News

© 2026 Created by Barnmice Admin.

Powered by

![]()

-

Quick Links

- Horse Blogs

- Horse Forums

- Horse Videos

- Horse Photos

-

Sister Sites

- The Rider Marketplace

- The Rider

- Equine Niagara News

-

Helpful Links

- Advertise With Us

- Barnmice Tour

- Feedback

- Report an Issue

- Terms of Service

© Barnmice | Design by N. Salo